The Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) is the world's largest surviving carnivorous marsupial. It has a thick-set, squat build, with a relatively large, broad head and short, thick tail. The fur is mostly

wholly black, but white markings often occur on the rump and chest. The body size varies greatly, depending on the diet and habitat. Adult males are usually larger than adult females; the large males weighing up to 12 kg and standing about 30cms high at the shoulder.

Devils once occurred on mainland Australia, with fossils having been found widely, but it is believed the devil became extinct on the mainland some 400 years ago - prior to European settlement. They possibly became extinct there due to increasing aridity and the spread of the dingo, which was prevented by the Bass Strait (the sea between the Australian mainland and the island of Tasmania) from entering Tasmania.

The Tasmanian devil cannot be mistaken for any other marsupial. Its spine-chilling screeches, black colour, and reputed bad-temper, led the early European settlers to call it the Devil. Although only the size of a small dog, it can sound and look incredibly fierce.

Today the devil is a Tasmanian icon but it hasn't always held this status. Tasmanian devils were considered a nuisance by early European settlers of Hobart town, who complained of raid on poultry yards. In 1830 the Van Diemen's Land Co., introduced a bounty scheme to remove devils, as well as Tasmanian tigers and wild dogs, from their northwest properties: 2/6d (25 cents) for male devils and 3/6d (35 cents) for the females. For more than a century, devils were trapped and poisoned and became very rare, seemingly headed for extinction. The population gradually increased after they were protected by law in June, 1941.

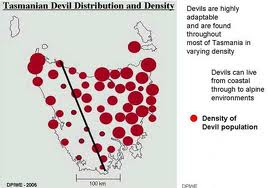

Anecdotal evidence suggests that devil numbers were quite variable over the past century but were at historic highs about 10 years ago. They were particularly common in forest, woodland and agricultural areas of northern, eastern and central Tasmania. These numbers have dropped since the 1995 identification of Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) - a fatal condition in Tasmanian devils, characterised by cancers around the mouth and head. (I won't show a picture as it is very distressing to see what happens to the poor creatures that contract this disease). There has been a 64% decline in spotlight sightings since the disease emerged. In the north-east of Tasmania. where signs of the Tasmanian devil disease were first reported, there has been an approximate 95% decline of average spotlight sightings from 1993-95 to 2002-2005.

Despite the decline in numbers in the past 10 years, populations of Tasmanian devils remain widespread in Tasmania from the coast to the mountains. They live in coastal heath, open dry sclerophyll forest, and mixed sclerophyll-rainforest - in fact, almost anywhere they can hide and find shelter by day, and find food at night.

Devils usually mate in March, and the young are born in April. Gestation is 21 days. More young are born than can be accommodated in the mother's backward-facing pouch, which has 4 teats. Although 4 pouch young sometimes survive, the average number is 2 or 3. Each young, firmly attached to a teat, is carried in the pouch for about 4 months. After this time the young start venturing out of the pouch and are then left in a simple den -often a hollow log. Young are weaned at 5 or 6 months of age, and are thought to have left the mother and be living along in the bush by late December. They probably start breeding at the end of their second year. Longevity is up to 7-8 years.

The devil is mainly a scavenger and feeds on whatever is available. Powerful jaws and teeth enable it to completely devour its prey - bones, fur and all. Wallabies, and various small mammals and birds, are eaten - either as carrion or prey. Reptiles, amphibians, insects and even sea squirts have been found in the stomachs of wild devils. Carcasses of sheep and cattle provide food in farming areas. Devils maintain bush and farm hygiene by cleaning up carcasses. This can help the risk of blowfly strike to sheep by removing maggots. Devils are famous for their rowdy communal feeding at carcasses- the noise and displays being uste do establish dominance amongst the pack.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

T also stands for TASMANIAN TIGER (Thylacinus cynocephalis) which is considered to have become extinct in 1936. Modern history records this thylacine as being native to Tasmania but scientists believe it was once widespread throughout mainland Australia, Tasmania and even Papua New Guinea.

The main evidence for this belief is the presence of thylacine-like animals in aboriginal rock art from northern Australia, including the Kimberley region of Western Australia., the Upper East Alligator region of Deaf Adder Creek and Cadell River crossing in the Northern Territory. Numerous thylacine bones have been found in mainland Australia and some of these bones have been dated at about 2,200 years old. Although we can't be sure what happened to the thylacines of mainland Australia and Papua New Guinea, scientists suspect that competition for food, and predators such as the dingo had a lot to do with their disappearance.

By the time Europeans settled in Australia the thylacine was only found in the coastal and plains regions of Tasmania. Thylacines were quite common and widespread when Tasmania was first settled in 1803, and the aboriginal people of Tasmania used the thylacine as a food item. Although commonly called the Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Wolf, the thylacine has more in common with its marsupial cousin the Tasmanian devil. With a head like a wolf, striped body of a tiger and backward facing pouch like a wombat, the animal was as unbelievable as the platypus which had caused disbelief and uproar in Europe when it was first described.

The thylacine looked like a long dog with stripes, a heavy stiff tail and a big head. A full grown animal could measure 180cm from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail, stand 58cm high to the shoulder and weigh about 30 kilograms. It had short, soft fur that was brown except for the thick black stripes which extended from the base of the tail to the shoulders. The name 'tiger' refers to the animal's stripes and not its temperament as it was a shy and secretive animals that avoided contact with humans. When it was captured it usually gave up without a struggle and many animals died quite suddenly, probably from shock. They were carnivores and reported to be relentless hungers who pursued their prey until the prey was exhausted. Like the dingo, the thylacine was a very quiet animal although they are reported to have made a husky barking sound or loud yap when anxious or excited.

The thylacine was said to have an awkward way of moving, trotting stiffly and not moving particularly quickly. They walked on their toes like a dog but could also move in a more unusual way - a bipedal hop. The animal would stand upright with its front legs in the air, resting its hind legs on the ground and using its tail as a support, exactly the way a kangaroo does. Thylacines had been known to hop for short distances in this position.

This is a photo of the last Tasmanian Tiger taken at the Hobart Zoo. It died on 7 September, 1936.(Image courtesy of Education Tasmania).

Extinction seems to have come quickly to this delightful animal which 100 years earlier was quite common. In 1824, settlers introduced sheep to the rich grazing lands in Tasmania. To the thylacine, more used to hunting swift moving prey such as kangaroos and birds, the sheep must have seemed like a much easier meal. In 1830, the Van Dieman's Land Company offered a bounty for the scalp of each thylacine and a further bounty was offered by the Tasmanian government in 1888. Between then and 1909, the government paid more than 2,180 bounties. By 1910 the once-common thylacine was considered rare and zoos from all over the world were keen to have one in their collection. Unfortunately, not many thylacines lasted long in captivity. Habitat destruction and a distemper-like disease further decreased the population until the last thylacine was captured in 1933. This animal was kept at Hobart Zoo until its death in 1936. The accepted story is that the day-shift keeper forgot to lock the thylacine up in its hut one night and it died of exposure. This seems such a sad ending for a beautiful animal.

There have been 'sightings' of what has been thought to be Tasmanian Tiger(s) on the mainland but these sightings have never been verified. One can only hope that perhaps somewhere the Tassie Tiger lives on.

Should you wish to read more about reported sightings and/or proposed cloning etc there is a very good website: http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/tasmanian-tiger

We can only hope. Hope that there are still at least a few Tasmanian Tigers and hope that a cure is found for those dreadful tumours.

ReplyDeleteAnother fascinating post - megathanks.

I've always thought these little Devils look cute, I mean, look at the two little ones there! I bet they'd give a nasty bite though!

ReplyDelete